Mention the terms “graphic novel” or “comic book” and most adults visualise either a handful of colourfully clad superheroes (i.e., Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman) or those classic black-and-white characters in the daily newspaper. Comic books, and their lengthier counterpart the graphic novel, however, have a much broader range of subject matter, style, and genre.

To put it simply, a comic book is any form of literature that combines story and art. Yes, that’s right, any form of literature. Like movies, books, and television shows, comics and graphics novels are an expandable medium—not a genre. This medium includes those heroic superhero adventures, of course, but also graphic nonfiction, realistic fiction, sports stories, fairy tales, and much more. And Raintree has them all!

Well, the differences are slim—literally. As Professor Nancy Frey, Ph.D., points out in her book Teaching Visual Literacy, “All graphic novels are comic books, but not all comic books are graphic novels.” The only real difference separating them is the length: comic books are slim volumes of stories told through sequential art (often serialized, 32-page pamphlets published monthly and sold directly to comic shops); graphic novels are simply longer versions of the same format.

Despite this definition being widely accepted, the term “graphic novel” is still debated among librarians, publishers, and the creators themselves. In fact, many of today’s top creators believe the terms “graphic novel” and “comic book” can be used interchangeably when discussing forms of literature that combine story and art.

Never read a graphic novel before? Don’t worry! As Superman once said, “You asked for my help. That’s all that matters.” Getting up to speed on this format is simple. Knowing a few key terms and definitions will give anyone a better understanding of the eccentricities and opportunities that graphic novels have to offer young readers.

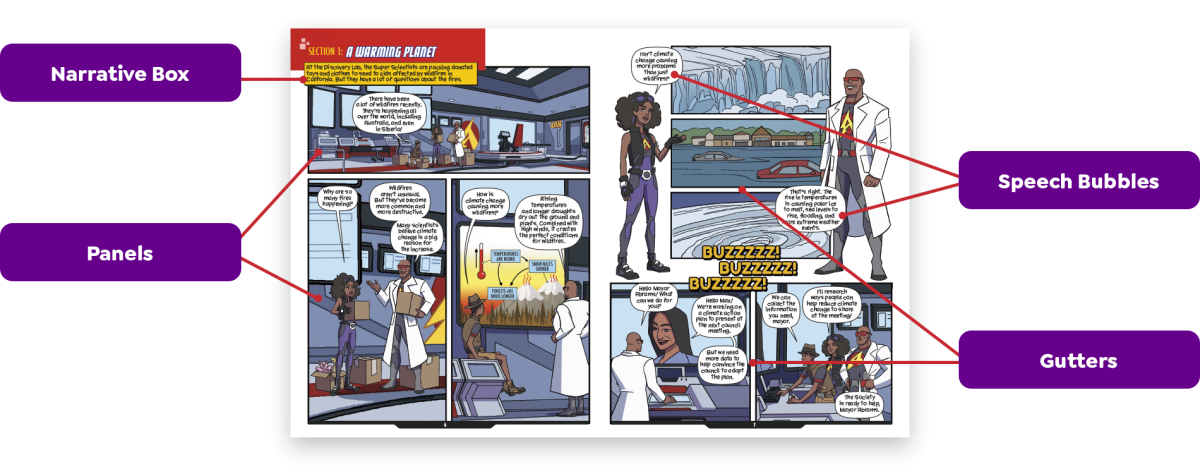

![]() Narrative Box

Narrative Box

Narrative boxes are slim, rectangular boxes—often located at the top or bottom of an illustrated panel— that convey information that cannot be communicated through character dialogue. Narrative boxes replace the four rhetorical modes of discourse seen in traditional text: exposition, argumentation, description, and narration.

![]() Panels

Panels

All graphic novels are made up of a series, or sequence, of illustrated frames called panels. Each frame is a subdivision of the entire composition, a piece of the larger puzzle. The number of panels, or illustrated frames, per page varies greatly from book to book.

![]() Speech Bubbles

Speech Bubbles

Also known as “dialogue balloons,” speech bubbles are the voice of comics. These often cloud-shaped bubbles emanate from the mouths of superheroes and other characters and communicate their dialogue throughout a graphic novel. Through width variation or altering a speech bubble’s shape or line type (wavy, jagged, dashed, etc.) dialogue balloons can also convey a character’s tone, timbre, or even his or her emotional state of mind.

![]() Gutters

Gutters

The gutters of comic books are the spaces in between the panels—the gap between each illustration in a story of sequential art and support foundational reading and writing skills, as they encourage students to anticipate, ask questions, and decipher the events between each of the panels on a comic page.

For many years, teachers, librarians, and readers have argued for the educational benefits of graphic novels. In fact, in an editorial for the New York Times in 1949, Lawrence K. Frank wrote, “Some day when the schools learn to use the dynamics of children’s spontaneous interest for learning, children will be permitted to discuss comics in the classroom.”

Despite this long-ago prediction, graphic novels and comic books remained absent in educational spaces for decades to come however the benefits of graphic novels for young readers can no longer be denied.

![]() Children Are Drawn to Comics

Children Are Drawn to Comics

One of the greatest advantages of graphic novels is their motivating factor. Studies show a dramatic increase in readership and circulation when comics and graphic novels are added to school libraries. In fact, School Library Journal reported that the mere presence of comics increased library usage by a whopping 82%! In addition, the circulation increase did not solely affect the comic shelves; the circulation of non-comic materials increased by more than 30% as well.

![]() Graphic Novels Motivate Challenged Readers

Graphic Novels Motivate Challenged Readers

Educators have distinguished two types of challenged readers: reluctant readers and struggling readers. Reluctant readers have the capabilities required for strong literacy skills, such as visualization, pronunciation, and vocabulary, but may lack the simple motivation to grab a book off the shelf. Often, literacy refusal stems from peer pressure, or the age-old perception that books are “uncool.” Instead of sparking a negative reaction, however, comics are often viewed as the “anti-book” books. The rebellious nature of the medium alone motivates kids to read. For this reason, graphic novels also make the perfect entry points for curriculum topics, including history, science, and even classic literature.

Unlike reluctant readers, motivation alone may not yield significant improvements for struggling readers. These students often have difficulties visualizing images in their minds by simply decoding words on the page. After failing to succeed with text-heavy chapter books, these students might give up on reading and become reluctant readers themselves.

![]() Visuals Support Readers

Visuals Support Readers

The pairing of visuals with words is perhaps the most obvious reason students read comics and graphic novels in the first place. And, studies have shown, that struggling readers greatly benefit from reader supports, such as pictures or illustrations that directly reflect the text.

In her book, Graphic Novels in Your Media Center, media specialist Allyson A. W. Lyga agrees, stating, “[Struggling readers] can focus their mental energy on gaining meaning from pictures (and, thus, understanding the story) rather than becoming frustrated by text that constantly challenges their inability to create mental pictures of the story.” Visual supports are especially helpful for younger readers. For this reason, publishers are bringing the format to an even younger audience: early readers, ages four to eight.

With many other benefits, graphic novels are a great choice for readers of all ages and literacy levels, from pre-readers to advanced. Their strong appeal, motivational value, and reading supports make them a key to unlocking any child’s reading superpowers. And Raintree's catalogue and website are the perfect places to start this adventure!